Words matter

A few weeks ago, the release of the draft of the document proposing guidelines for inclusive communication in the European Commission generated, in Italy and in Europe, a series of controversies for an alleged attempt to “cancel” Christmas.

The document was titled “#UnionOfEquality – European Commission Guidelines for Inclusive Communication.” The offending passage was in the section on “cultures, lifestyles, or beliefs”.

After suggesting to avoid “assuming everyone is a Christian” and to consider “that people have different religious traditions and calendars,” among the examples of expressions to avoid saying or writing was, “Christmas season can be stressful”. With a suggestion to replace it with, “The holiday season can be stressful”. A generic “holidays,” rather than “Christmas,” in short.

Beyond the possible polemics, the issue makes us think. Do we think that only in this way, by replacing words that refer to fundamental moments of a culture or religion, with bland synonyms, can we arrive at a real inclusion between different people? How can ancient words, with deep roots, help to build a truly inclusive society, without necessarily having to “cancel” them?

As we breathe and share the stories we host on this portal, we have learned that diversity is not an obstacle, but can become an opportunity for reflection, greater understanding, mutual enrichment and, if embraced, can help build a truly inclusive society. So too words, if heard.

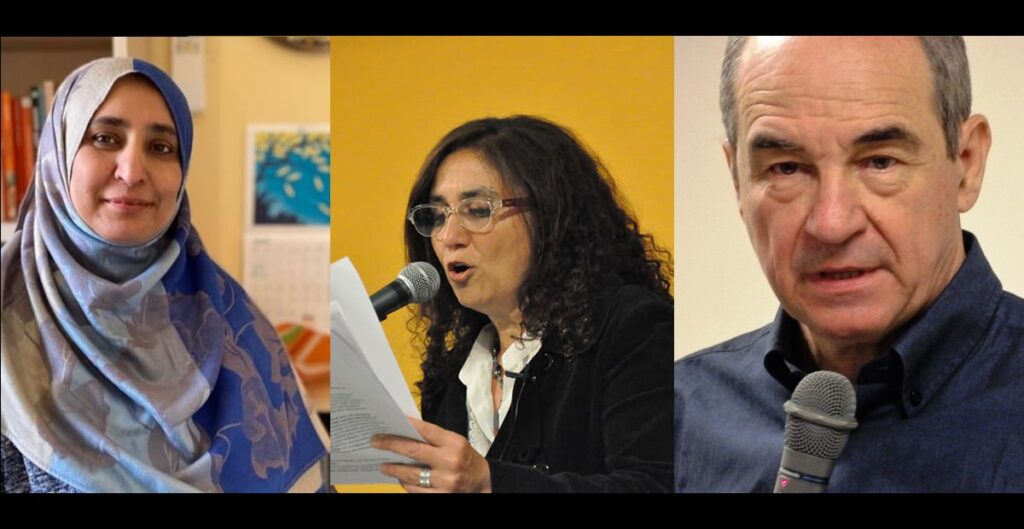

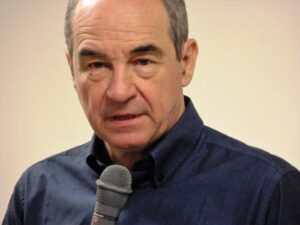

We shared our questions with some of the key players in these stories: Haifa Alsakkaf, Italian-Yemeni, Muslim, director of the non-profit organization Good World Citizen; Roberto Catalano, Italian, Christian Catholic, expert in interreligious dialogue, professor at Sophia University Institute; Silvina Chemen, Argentinean and rabbi of the Jewish community “Bet-El” of Buenos Aires. These are their contributions that we offer to enrich everyone’s reflection.

Haifa Alsakkaf, director of Good World Citizen

Words certainly matter, they define us, they are our primary means of communication. Often, the problem lies in the fact that many terms have lost their real value and have become sounds that are repeated without knowing their meaning. Even words that carry a religious and spiritual meaning are often emptied of their deep meaning, becoming just a folkloric term that we hear and repeat on certain occasions. It is wrong to try to cancel these words; on the contrary, we need to give them back their full value and meaning. I don’t think there is anyone who would be offended or discriminated against if they hear “Merry Christmas” or “Ramadan Mubarak” if they know the meaning of those words and the value they carry.

An inclusive society welcomes all people with their cultural baggage, which also includes many words referring to religious, cultural, linguistic, identity or other aspects. A truly welcoming and inclusive society safeguards the uniqueness of each person and makes each person’s experience meaningful, in addition to belonging to a broad and composite community. It takes an intercultural approach in which there is a process of open and respectful exchange of views between different people and groups in a spirit of mutual understanding and respect. It is an encounter between different worlds or points of view and with the goal of getting to know each other and cooperating for positive change.

It is now a fact that we live in multicultural societies and that we are all subject to different cultural experiences and influences. Each person is the bearer of many riches and values and can make a positive contribution to society and to the people around them and whom they meet every day. The encounter with the other, with the subject ethnically and culturally different, represents a challenge, a possibility of exchange and reflection and, above all, an advantage and an opportunity for enrichment for the whole society.

Roberto Catalano, expert in interreligious dialogue, professor at Sophia University Institute

Once again, this year, as Christmas approaches, the age-old controversy over the typical symbols of Christian Christmas returns: should we eliminate them out of respect for the new religious presences in the West, or keep them?

The issue is destined to last and to be enriched by tensions and controversies. Because at the root of these misunderstandings lie not so much the identities of others as our own. It should be emphasized that, with all the problems and issues related to them, migrants or those who have long since moved to our continent have their own identity. Especially if they are Muslims. It is we, instead, who are rather confused. It is interesting to note, in fact, that the various proposals and polemics have never arisen from complaints from ‘others’, but rather from local people or groups, from our own home. They usually arise from the secular – or better, secularist – Western world which, in the name of a coated desire to ensure the social integration of groups belonging to other cultures and religions, tends to flatten Western identity and its Jewish-Christian roots. Behind these attitudes, there is no respect for others, but rather a desire to flatten religious sentiment. It is the long wave of the legacy coming from the relativism of the Enlightenment. Faced with these polemics and the climate they stir up, people of other faiths find themselves even more disoriented on our Continent. They lack, in fact, the possibility of having clear references.

Knowing that we are in a part of the world where the birth of Jesus is celebrated is not disturbing. Let’s keep in mind that Jesus is a Prophet in Islam. And, on the other hand, this clarity allows newcomers to celebrate their own holidays such as Ramadan for Muslims or Diwali for Hindus, or, again, the myriad of other holidays in the Jewish, Buddhist, Sikh traditions and so on, freely and without problems. Identity is never an obstacle, especially if it is welcoming and open to others, to the culturally and religiously ‘different’. The problem lies in wanting to impose our identity on others and with it our own culture and religion. Exactly what the West has done for centuries and, in a certain sense, continues to do today with its secular – or, as I mentioned, secularist – culture, which does not admit differences in the face of an apparent neutral image in terms of religion. Without knowing who they are or who we are, it is impossible to have relationships and dialogue. Let us, therefore, be careful not to deceive ourselves with false problems that arise from a deep identity vacuum from which we suffer in the West.

Silvina Chemen, rabbi of the Jewish community “Bet-El” of Buenos Aires

At the dawn of social communication, there is an ancient question of whether reality exists beyond language or whether language generates realities.

Naturally, I never make exclusionary choices. And I tend to think that language affects reality, empowers the emergence of new concepts, but that, with militancy applied to language alone, nothing is achieved.

Inclusion presupposes the abolition of all barriers and really making room for that “other,” who was previously not allowed as part of our environment.

Inclusion means changing old ways of doing things, accepting the novelty of the time, discussing the topic in depth and taking responsibility for such an important decision.

I mean to say that attempting to modify language highlights our habits of speaking and writing, which take for granted realities that need to be re-examined.

In summary, if religious life were more egalitarian in terms of rights and vocations, there would be no need to change a millennial language and practice born in a hetero-normative and patriarchal environment from which stories, characters and rituals are derived. Jesus, a man, was born with a mission that was not just for men. This is what needs to be understood first and foremost.

In order to build a truly inclusive society, even through words, a sincere paradigm shift is needed, which is happening in many areas. The expansion of women’s rights around the world, their struggles for equal access to education and employment opportunities are well known and are bearing fruit, though not all as hoped for, for the moment.

The fact is that when fighting for inclusion, the commitment must be made to all the excluded. What is the point of opening the priesthood to women if migrants continue to die on boats in the Mediterranean?

The paradigm shift also involves a firm political commitment to inclusive education, inclusive media policy, inclusive state management, and, of course, economic policy in which no sector is left on the sidelines.

Unfortunately, it is the most excluded sectors that take charge of their own struggles to protect or extend rights.

However, a truly inclusive society is one that advocates for the interest and well-being of anyone who is discriminated against, forgotten, or silenced.

The fight for gender equality should not be a women’s fight.

The fight for social and economic equality should not be a fight of the poor.

The fight to settle in a country that welcomes them should not be the fight of migrants.

The pandemic has shown that the whole world is sick, and we have not understood that if rich countries continue to keep vaccines for them and the poor continue to get sick, there is no rich who can save themselves.