Workshop

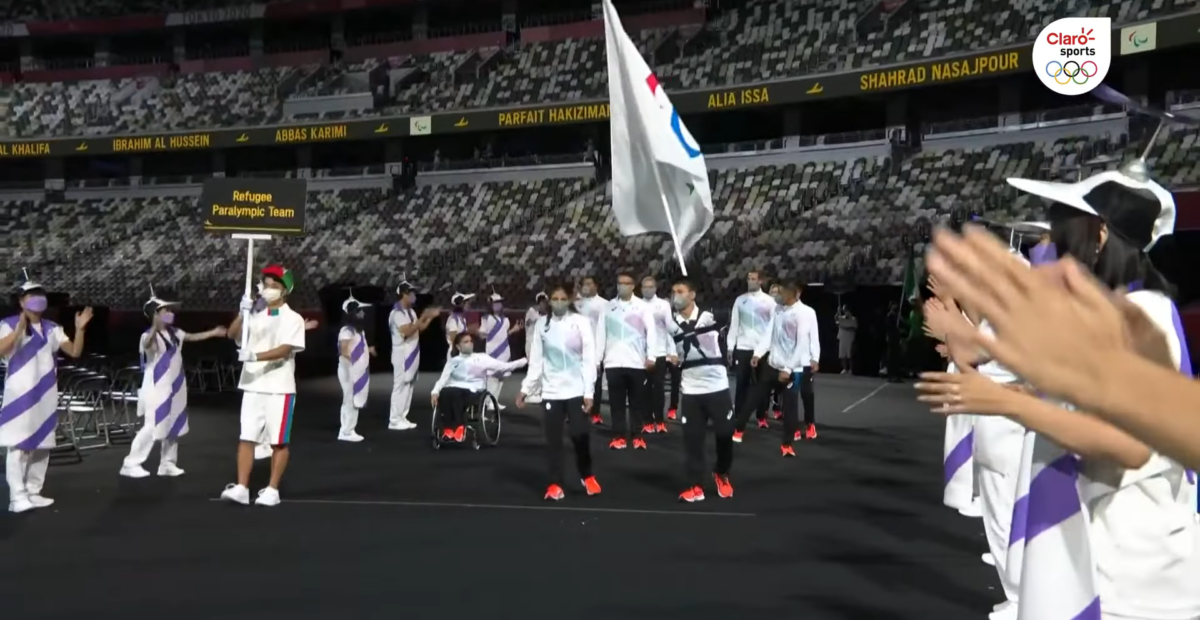

Hope and Resilience, the Example of the Olympic Refugee Team

For the second time in history the Olympic Refugee Team participated in the Olympic Games. It was a symbol of hope for migrants and refugees from all over the world. We share some of their stories of hope and resilience because we believe that the united world also involves making their stories our own.

There were 29 athletes on the Olympic Refugee Team in Tokyo 2020. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) defined a refugee as “someone who has been forced to flee their country due to persecution, war or violence”. Therefore, it represents over 20 million people who are from their own countries.

The first Olympic Refugee Team made its debut at the 2016 Games in Rio. Thomas Bach, President of the International Olympic Committee, then declared: “By welcoming the Olympic Refugee Athletes team to the 2016 Rio Games, we want to send a message of hope to all the refugees of the world. It is also a signal to the international community: refugees are like us and are a wealth for society. These athletes will show the world that despite the unimaginable tragedies they have had to face, they can contribute to society through their own talent, ability and strength of spirit.”

The experience repeats itself this year at Tokyo 2020. The 29 athletes of the Refugee Team practice 12 sports: athletics, badminton, boxing, canoeing, cycling, judo, karate, shooting, swimming, taekwondo, weightlifting, and wrestling. They come from 11 countries: Afghanistan, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, the Republic of the Congo, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria and Venezuela. Most of them are supported through scholarships from the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

Here are some of their stories:

Ali Zada is an Afghan cyclist. When she rode her bicycle, as a child, people threw stones and fruit at her, and shouted insults. In 2016, she and her sister Zahra took part in a race at Albi, France, and their story was told in a documentary called The Little Queens of Kabul. In 2017, they obtained asylum with their family and moved to Lille. “I couldn’t ride a bicycle in Afganastan, because it was forbidden. I never saw a girl on a bicycle, much less in sport clothes. At the time, there weren’t many girls on bicycles and people were agressive when they saw us. They thought it was against our culture and our religion, but that’s not true. It’s just that it was weird for them to see a woman on a bicycle for the first time. I’ve never given up on cycling. On the contrary, I want to encourage girls to do it and normalize women’s cycling in Afghanistan” (actu.fr, 12 June 2021; infomigrants.net, 06 June 2021; marca.com, 11 January 2021). Ali Zada chose to wear the veil while competing: “People comment on my veil. They ask me if I’m not too sexy. (We can never stop educating people.) I live alone in Lille, my parents are in Orleans, and my father always told me it was up to me to decide whether I wanted to wear the veil or not. This is something people just don’t understand.” (actu.fr, 12 June 2021)

Popole Misenga, the Judoka

Popole is originally from Bukavu, the area most affected by the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (1998 – 2003). When he was nine years old, he lost his family and was found after eight days wandering alone in the jungle. He discovered judo at the Kinshasa orphanage that took him in. He says: “When you’re a child, you have to have a family that gives you instruction on what to do, and I didn’t have one. Judo helped me by giving me serenity, discipline, commitment – everything.” But Misenga also suffered persecution and punishment. In 2013, fearing for his life, he asked for asylum in Brazil while he was in Rio de Janeiro for the World Judo Championships. He obtained asylum in 2014 and in 2016 was selected for the IOC Refugee Olympic Team: “It meant a lot to me being able to represent all the refugees of the world on the international sports platform. It gives me strength on the mat, representing the millions of people who have had to leave their home and country. Judo saved me”.

Sanda Aldass, the Joduka

Sanda Aldass is 31 years old, and she is also a judoka. She comes from the city of Damascus in Syria. Sanda and her family lost their home during the war. In 2015, she fled through Turkey to the Netherlands, anticipating her husband Fadi Darwish who is also her coach. You spent nine months separated from your family in a refugee camp.

“I spent all my time running and doing exercises, which also kept me in good mental health,” she says. “I knew that they would eventually arrive, and we’d have a good place to live.” Now Darwish is her official coach, and the family has grown. They have three children. The International Judo Federation invited the couple into their training program refugee athletes in 2019 with Aldass competing as judoka of the IJF Refugee Team at that year’s World Championships.

Since then, he has also represented the team at Grand Slam events while aiming for a potential spot at the Olympic Games. Goal achieved!

Fazloula Saeid and the canoe

Fazloula Saied is 28 years old. In the past, he represented the Islamic Republic of Iran, but during the 2015 World Championships in Milan, Italy, he took a selfie in front of the city’s famous Dome church. Because of this you received threats in the Islamic Republic of Iran because of religious reasons. That year you fled via the Balkan Route to Karlsruhe, Germany. In 2018, he started competing for Germany, where he was recognized as a political refugee. He explains: “I had everything I wanted in Iran: money, a car and an apartment. At first, the only thing I could do in Germany was canoe. As soon as I pick up the paddle, I forgot all my worries. Initially, when I lived in a refugee home, I was happy to be able to go to the club and stay there until the evening. The canoe calms me down.” (thefrontierpost.com, 01 June 2021; swr.de, 08 June 2021; canoeicf.com, 08 June 2021; insidethegames.biz, 01 October 2020; IOC Refugee Olympic Team Instagram profile, 22 April 2021). In 2018, he was named a sports hero by German broadcaster Sudwestrundfunk: “If there’s one thing I always tell myself, it’s this: I just have to believe I’ll do it, whatever it may be.” (thefrontierpost.com, 01 June 2021).

Lohalith Anjelina Nadai

Anjelina arrived with her aunt, in the refugee camp of Kakuma, Kenya, in 2002. They were fleeing from South Sudan due to the war. Her teachers noticed her talent while she was still living in the refugee camp. In 2015, one of her teachers invited her to take part in a 10 km run organized by the Tegla Loroupe Foundation, the foundation of the former middle-distance runner and marathon runner whose purpose is to support and encourage projects in favor of conflict resolution, peace and the reduction of poverty in the Great Lakes region. Given her results, Anjelina was selected and since then has been training with the Foundation. “Wherever I went, I ran,” she recalls in an interview (mobsports.com, June 18, 2021). “When I went to get something for my mother, I ran because I didn’t want to be beaten by her. I liked running for no reason, but I didn’t know anything about running until Tegla arrived on the field. I didn’t know who he was. I only found out about his medals and his world record.” Anjelina participated in the Rio 2016 Olympic Games. In 2018, she was selected to join other young people from around the world in the first “Sports at the Service of Humanity – Young Leaders Mentoring Program,” mentoring for young leaders) in view of the “Olympism in Action” Forum of the International Olympic Committee and the Youth Olympic Games in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

After her participation in the 2016 Olympic Games, she became a mother.