Workshop

“We must replace the word ‘inclusion’ with ‘participation'”. Talking about disability with Beppe Porqueddu

On the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, Beppe Porqueddu shares his inspiring testimony on how he turned his pain into an engine of social and cultural change. After an accident that made him paraplegic in 1970, his life took a radical turn, becoming a reference in the field of rehabilitation and accessibility.

For the International Day of Persons with Disabilities – today, 3rd of December – we have gathered the valuable testimony of Beppe Porqueddu. It all started on December 16, 1970, when, due to a serious car accident, Beppe became paraplegic. We began from that moment, which marked the start of a journey filled with commitment, experiences, and sharp, clear reflections on the topic. Beppe has carried out his mission for many years, becoming a rehabilitation technologist at a major center in Rome. He is an extremely knowledgeable person in the field of disabilities.

Beppe, do you feel like rewinding the thread and narrating to us your story?

That December 16th was an important, unexpected “detail.” I found myself on the ground after colliding with a truck that had stopped on the road I took every morning to go to school, on my scooter, from Porto Torres to Sassari, in Sardinia. I felt like I was dying, and two images surfaced in my mind, like two mirrors facing each other: my life up to that point and life from that moment onward. I understood the significance of that dramatic moment: I had to say yes. I had to respond to the newness that awaited me. The two mirrors dissolved, and my path was born up to today.

But there was a difficult moment, a moment of discouragement, when at your university you encountered hostile architecture, if I can put it that way.

After completing the third year of high school, during my second year of paraplegia, the harmonious life I lived internally, despite the change in my physical condition, clashed with society. At my university, a contrast emerged between the beauty within me and the beauty that was unattainable outside. I was happy to be alive, but I couldn’t find external elements that embraced my new condition. I had accepted it, but the external environment had not. From this, I felt a wave of nausea under the university stairs one day.

In front of an architecture that, in one of your many speeches at conferences, you define “of non-love.”

That architecture expressed a culture, because architecture is always culture. I felt that neither of them had anticipated me.

A painful awareness

Of a cultural pain: that wave of nausea did not arise within me from internal issues of non-acceptance. But from something external that I had to remove.

And you drew fruit from this experience.

From there my commitment to disability issues arises, which were not addressed as they are today. The very word disability did not exist. Yet, thanks to that value-laden and spiritual background, I experienced this drama as luminous, even though it was complex.

In what sense?

Between 1971 and 1977, I kept asking myself: “Why am I happy with the troubles I have?” I was in a tunnel, but a very bright one. I felt completely inside the disability, but also outside of it.

Can we say that the light came from within and the darkness from outside?

There was something that opposed my intimate, inner progress. To my human realization: it was the pain that was removed, not loved by culture. A non-love for pain and for the people who experienced it. If there are barriers instead of facilitations, there is a reason! It is not random.

When you witnessed the accident, you were a young member of the Focolare movement

Yes, and my story has always been lived in unity. Never as a solitary experience. Always within the large Focolare family and in the value-laden background that is the charisma of unity. In the idea of a united world and a new world. In all of this, what happened to me was inserted. Soon, I became aware of pain as a relational, social, and cultural fact.

Let’s return to the word “detail” that you used at the beginning:

In the large family of the Focolare movement, youth were growing up. They had been entrusted with a social heritage, as well as a spiritual one. For this reason, the accident, however significant, was a detail, because I was already living a great ideal. The accident and the disability were part of this big vision: what mattered was the idea of a united and new world, with a new anthropology that was advancing, in a context where disability was embraced, conceived, and transcended.

Thanks to Chiara Lubich, founder of the Focolare Movement.

Chiara sensed that there was something new in my story. She saw it clearly and said: “We must make a new revolution. Give value to pain, but not in a pietistic sense.” From there, I understood that pain is a great spring of change, transformation, and evolution itself.

So, through this detail, through the suffering from that cultural pain, you began to work on what you define, in one of your speeches at conferences, as “perceptual education of designers.” What is it about?

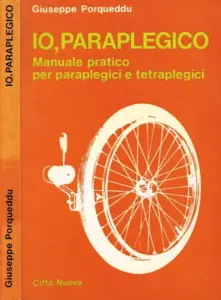

When meeting people with disabilities, I realized that they had not undergone the rehabilitation process that I experienced in Geneva, at a specialized center, thanks to Chiara Lubich. They sent me there, where I acquired many skills, and during a trip to Lourdes, I met a paraplegic person who told me she was not independent at all. She had met with an accident 15 years earlier when she was already a mother of a little girl. I taught her how to get into bed by herself, in a wheelchair or in the bathtub. I understood even better the magnitude of a collective, social problem. So, I began to prepare informative handouts for paraplegics. From there, a book was born, later published by “Città Nuova”: the first Italian manual on tetraplegia and paraplegia. “Io paraplegico. Manuale pratico per paraplegici e tetraplegici” (“I Am Paraplegic: A Practical Manual for Tetraplegics and Paraplegics”), also published in Spain.

Another important milestone in the journey.

From there, I became known and invited to speak at conferences, and my social development life began. I started to be part of interdisciplinary teams for the training of architects, surveyors, and engineers, because the issue of barriers, or accessibility, was already becoming apparent. Although this word, much more evolved and positive, came later.

Other steps?

I met a woman: a very important architect. She had written books and involved me in an initial training course for architects, surveyors, and engineers in Piemonte. A great intellectual partnership was born, and I began to understand that there was a need for training on disability understood as a cultural perspective. But it had to address two frontiers.

Which ones?

A more technical-cultural one; the other more intimate, inner, psychological, and spiritual. Both concerning the designer. To work, indeed, on that pain removed by culture. It was necessary to recreate the mindset of designers, of architects who were already professionals and of new generations, with attention to disability from the early years of architecture school. In a great creative perspective.

From there, indeed, what you called “perceptual education.”

On which I built projects for public administrations in various places in Italy. Especially in Val d’Aosta, where I began to take care, in depth, of the education of the designer. A collective path, carried out with other teachers to invent a new design prototype.

Among the various conferences you have attended, there is one recently coordinated, especially aimed at youth, on physical movement. The title is ‘Water, Movement, Health,’ in which the theme discussed was: ‘We are bodies for relational sustainability.’ Can you describe it?

The conference was organized with Onda Blu, a cooperative from Belluno founded in 1994. Since 1984, I have been part of that territory and participated in the creation of the Prisma Study Center, particularly collaborating with my dear friend Renzo Andrich, an engineer and a young member of the Focolare Movement, like me. He, too, is dedicated to working with disabilities. Together, we have carried out a significant cultural and human journey.

Can you tell us more about it?

We have implemented several innovative projects for the education of autonomy for people with physical disabilities. In Belluno, a lot of work has been done through aquatics. Onda Blu needed the sensitivity of the Prisma Study Center towards disabilities, and in the mentioned conference, where I was part of the scientific group and wrote the introductory report, we focused on a theme that is currently a priority for human health: physical movement.

Interesting.

The theme of health fits into the framework of expressiveness, creativity, physicality, and sociality: foundational pillars of human personality and the approach to disability. But health also fits into the framework of sustainability: one cannot be healthy with polluted air, thus health is sustainable with care for the environment, including the architectural environment. Obviously, disability is also integrated into this holistic vision of humanity.

Your reflection reminds me of the concept of integral ecology.

Health is a relational fact. That is why at the conference I cited many Paralympic athletes: it was a spectacle for me, an endless joy to observe the deepening integration, increasingly over the years, between their impairment and their full lives. When I felt nauseated in front of barriers, it was because that architecture was insufficient to welcome me. Today, seeing these beautiful, resolved, and happy people with disabilities, despite their amputations and impairments, we are witnessing an anthropological novelty: a point of arrival after a journey of thousands of years.

You used the word integration, not inclusion. Why?

Because inclusion says very little. The Latin verb “claudere,” which generates the words include and exclude, means to close inside or to close outside. I prefer to be in expansion. We should replace the word inclusion with participation, which has an enormous political meaning. Full participation, with full rights and full duties. It is legitimate to address the issue in terms of civil rights, but the topic is much more complex. It cannot be viewed only from the perspective of apartheid, but from the concept of unity, of the “whole.” We should not aim for a fragmented society, but for a unified vision. The problem lies once again in culture. Jesus speaks of the brother and not of the poor to be helped. Of equality. I do not use the words fragility, weakness, or limit in my texts. Seeing me in a wheelchair, many think I am a fragile person. I would not say so. On December 16, I will have been paraplegic for 54 years. Many people considered fragile show themselves to be the most courageous and stable, strong and resilient.

Watch this video to know more about Beppe Porqueddu and his journey: